This is an almost entirely copy of chapter 8 of the book Statistical Physics of Fields 1, just adding a little of my own understanding and online materials. It is mainly for me to do a presentation on the class of phase transition theory. Note that the last two sections are not included.

The nonlinear \(\sigma\) model

Consider unit $n$-component spins on the sites of a lattice, i.e. \(\vb*{s}(\vb*{i}) = (s_1, s_2, \cdots, s_n) , \ \text{with} \ \abs{\vb*{s}(\vb*{i})} = 1.\) The usual nearest-neighbor Hamiltonian can be written as \(-\beta \mathcal{H} = K \sum_{\ev{i, j}} \vb*{s}(\vb*{i}) \vdot \vb*{s}(\vb*{j}) = K \sum_{\ev{i, j}} \qty[1 - \frac{1}{2} (\vb*{s}(\vb*{i}) - \vb*{s}(\vb*{j}))^2] .\) At low temperatures, after replacing the difference with a gradient and assumimg the lattice spacing is a unit, we can get \(\begin{equation} -\beta \mathcal{H} = -\beta E_0 - \frac{K}{2} \int \dd[d]{\vb*{x}} \qty(\grad{\vb*{s}(\vb*{x})})^2 . \label{math:1} \end{equation}\) Note that there is a cutoff of $\Lambda \approx \pi$ in Eq. \(\eqref{math:1}\), and that the gradient only acts on space. Ignoring the ground state energy, the partition function is \(\begin{equation} Z = \int \mathcal{D} \qty[\vb*{s}(\vb*{x}) \delta \qty(\vb*{s}(\vb*{x})^2 - 1)] \ee^{- \frac{K}{2} \int \dd[d]{\vb*{x}} (\grad \vb*{s})^2} . \label{math:2} \end{equation}\)

A possible ground state configuration is \(\vb*{s}(\vb*{x}) = (0, \cdots, 1)\). Set \(\vb*{s} (\vb*{x}) = (\pi_1 (\vb*{x}), \cdots, \pi_{n-1} (\vb*{x}), \sigma (\vb*{x})) \equiv (\vb*{\pi}(\vb*{x}), \sigma(\vb*{x})) ,\) where \(\vb*{\pi}(\vb*{x})\) is an $(n-1)$ component vector. By using $\delta (ax) = \delta (x) / \abs{a}$, we can get \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \int \dd{\vb*{s}} \delta (s^2 - 1) &= \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \dd{\vb*{\pi}} \dd{\sigma} \delta(\pi^2 + \sigma^2 - 1) \\ &= \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \dd{\vb*{\pi}} \dd{\sigma} \delta \qty[\qty(\sigma - \sqrt{1-\pi^2})\qty(\sigma + \sqrt{1-\pi^2})] \\ &= \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{\dd{\vb*{\pi}}}{2 \sqrt{1 - \pi^2}} . \end{aligned} \end{equation}\) Now Eq. \(\eqref{math:2}\) can be written as \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} Z & \propto \int \frac{\mathcal{D} \vb*{\pi}(\vb*{x})}{\sqrt{1 - \pi(\vb*{x})^2}} \ee^{- \frac{K}{2} \int \dd[d]{\vb*{x}} \qty[(\grad \vb*{\pi})^2 + (\grad \sqrt{1 - \pi^2})^2] } \\ &= \int \mathcal{D} \vb*{\pi}(\vb*{x}) \exp \qty{ - \int \dd[d]{\vb*{x}} \qty[\frac{K}{2} (\grad \vb*{\pi})^2 + \frac{K}{2} \qty(\grad \sqrt{1 - \pi^2})^2 + \frac{\rho}{2} \ln(1 - \pi^2)] } . \end{aligned} \end{equation}\) In going from the lattice to the continuum, we have introduced a density $\rho = N/V = 1/a^d$ of lattice points.

We can expand the nonlinear terms for the effective Hamiltonian in powers of \(\vb*{\pi}(\vb*{x})\), resulting in a series \(\beta \mathcal{H} [\vb*{\pi} (\vb*{x})] = \beta \mathcal{H}_0 + \mathcal{U}_1 + \mathcal{U}_2 + \cdots ,\) where \(\beta \mathcal{H}_0 = \frac{K}{2} \int \dd[d]{\vb*{x}} (\grad \vb*{\pi})^2\) describes independent Goldstone modes, while \(\mathcal{U}_1 = \int \dd[d]{\vb*{x}} \qty[\frac{K}{2} (\vb*{\pi} \vdot \grad \vb*{\pi})^2 - \frac{\rho}{2} \pi^2]\) is the first order perturbation when the terms in the series are organized according to powers of $T = 1/K$. Since we expect fluctuations \(\ev{\pi^2} \propto T\), $\beta \mathcal{H}$ is order of one, the two terms in $\mathcal{U}_1$ are order of $T$; remaining terms are order of $T^2$ and higher. In the language of Fourier modes, \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \beta \mathcal{H}_0 &= \frac{K}{2} \int \frac{\dd[d]{\vb*{q}}}{(2\pi)^d} q^2 \abs{\vb*{\pi}(\vb*{q})}^2 \\ \mathcal{U}_1 &= - \frac{K}{2} \int \frac{\dd[d]{\vb*{q}_1} \dd[d]{\vb*{q}_2} \dd[d]{\vb*{q}_3}}{(2\pi)^{3d}} \pi_{\alpha} (\vb*{q}_1) \pi_{\alpha} (\vb*{q}_2) \pi_{\beta} (\vb*{q}_3) \pi_{\beta} (-\vb*{q}_1 -\vb*{q}_2 -\vb*{q}_3) (\vb*{q}_1 \vdot \vb*{q}_3) \\ & - \frac{\rho}{2} \int \frac{\dd[d]{\vb*{q}}}{(2\pi)^d} q^2 \abs{\vb*{\pi}(\vb*{q})}^2 . \end{aligned} \end{equation}\)

For the non-interacting (quadratic) theory, the correlation functions of the Goldstone modes are \(\ev{\pi_{\alpha} (\vb*{q}) \pi_{\beta} (\vb*{q}')}_0 = \frac{1}{K q^2} \delta_{\alpha \beta} (2\pi)^d \delta^{d} (\vb*{q} + \vb*{q}')\). The resulting fluctuations in real space behave as \(\ev{\pi(\vb*{x})^2}_0 = \frac{n-1}{K} \frac{K_d \qty(a^{2-d} - L^{2-d})}{d-2}\). The Mermin–Wagner theorem tells us it is the absence of long range order in $d \leqslant 2$ (no spontaneous continuous symmetry breaking).

To construct a perturbative RG (perturbative renormalization group), consider a spherical Brillouin zone of radius $\Lambda$, and divide the modes as \(\vb*{\pi} (\vb*{q}) = \vb*{\pi}^{<} (\vb*{q}) + \vb*{\pi}^{>} (\vb*{q})\). The mode \(\vb*{\pi}^{<}\) involve momenta \(0 < \abs{\vb*{q}} < \Lambda / b\), while we shall integrate over the short wavelength fluctuations \(\vb*{\pi}^{>}\) with momenta in the shell \(\Lambda / b < \abs{\vb*{q}} < \Lambda\). To order of T, the coarse-grained Hamiltonian is given by \(\begin{equation} \beta \tilde{\mathcal{H}} \qty[ \vb*{\pi}^{<}] = V \delta f_b^0 + \beta \mathcal{H}_0 \qty[\vb*{\pi}^{<}] + \ev{\mathcal{U}_1 \qty[\vb*{\pi}^{<} + \vb*{\pi}^{>}]}^{>}_0 + \order{T^2} \label{math:3} \end{equation}\) where $\ev{\ }_0^{>}$ indicates averaging over \(\vb*{\pi}^{>}\).

$\delta f_b^0$ is the zero order free energy density in \(\Lambda / b < \abs{\vb*{q}} < \Lambda\).

The quartic part of $\ev{\mathcal{U}_1}_0^{>}$ can be represented by Feynman diagrams by using Wick theorem. Let us skip the calculation. The coarse-grained Hamiltonian in Eq. $\eqref{math:3}$ now equals

\(\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\beta \tilde{\mathcal{H}} \qty[ \vb*{\pi}^{<}] =& V \delta f_b^0 + V \delta f_b^1 + \frac{K}{2} \qty(1 + \frac{I_d(b)}{K}) \int_0^{\Lambda / b} \frac{\dd[d]{\vb*{q}}}{(2\pi)^d} q^2 \abs{\vb*{\pi}^{<}(\vb*{q})}^2 \\

& + \frac{K}{2} \int \frac{\dd[d]{\vb*{q}_1} \dd[d]{\vb*{q}_2} \dd[d]{\vb*{q}_3}}{(2 \pi)^{3d}} \pi^{<}_{\alpha}(\vb*{q}_1) \pi^{<}_{\alpha}(\vb*{q}_2) \pi^{<}_{\beta}(\vb*{q}_3) \pi^{<}_{\beta}(-\vb*{q}_1-\vb*{q}_2-\vb*{q}_3) (\vb*{q}_1 \vdot \vb*{q}_3) \\

& - \frac{\rho}{2} \int_0^{\Lambda / b} \frac{\dd[d]{\vb*{q}}}{(2\pi)^d} \abs{\vb*{\pi}^{<}(\vb*{q})}^2 \qty[1 - \qty(1 - b^{-d})] + \order{T^2} ,

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}\)

where

\(\begin{equation}

I_d(b) = \int_{\Lambda /b}^{\Lambda} \frac{\dd[d]{\vb*{k}}}{(2\pi)^d} \frac{1}{k^2} = \frac{K_d \Lambda^{d-2} (1 - b^{2-d})}{d-2} .

\end{equation}\)

$K_d = S_d / (2 \pi)^d$, where $S_d$ is the $d$-dimensional space angle integral.

The most important consequence of coarse graining is the change of the stiffness coefficient $K$ to $\tilde{K} = K \qty(1 + \frac{I_d(b)}{K})$. After rescaling, $x’ = x/b$, and renormalizing, \(\vb*{\pi}'(\vb*{x}) = \vb*{\pi}^{<}(\vb*{x}) / \zeta\), we obtain the renormalized Hamiltonian in real space as \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} - \beta \mathcal{H}' =& - V \delta f_b^0 - V \delta f_b^1 - \frac{\tilde{K} b^{d-2} \zeta^2}{2} \int \dd[d]{\vb*{x}'} \qty(\grad' \pi')^2 \\ & - \frac{K b^{d-2} \zeta^4}{2} \int \dd[d]{\vb*{x}'} \qty(\vb*{\pi}'(\vb*{x}') \grad \vb*{\pi}'(\vb*{x}'))^2 + \frac{\rho \zeta^2}{2} \int \dd[d]{\vb*{x}'} \pi'(\vb*{x}')^2 + \order{T^2} . \end{aligned} \label{math:4} \end{equation}\) To obtain the rescaling factor $\zeta$, we utilize the rotational symmetry of spins. After averaging over the short wavelength modes, the spin is \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \ev{\tilde{\vb*{s}}}_0^{>} &= \ev{\qty(\pi_1^{<} + \pi_1^{>}, \cdots, \sqrt{1 - \qty(\vb*{\pi}^{<} + \vb*{\pi}^{>})^2})}_0^{>} \\ &= \qty(\pi_1^{<}, \cdots, 1 - \frac{(\vb*{\pi}^{<})^2}{2} - \ev{\frac{(\vb*{\pi}^{>})^2}{2}}_0^{>} + \cdots) \\ &= \qty(1 - \ev{\frac{(\vb*{\pi}^{>})^2}{2}}_0^{>} + \order{T^2}) \qty(\pi_1^{<}, \cdots, \sqrt{1 - (\vb*{\pi}^{<})^2}) . \end{aligned} \end{equation}\) We thus identify \(\begin{equation} \zeta = 1 - \ev{\frac{(\vb*{\pi}^{>})^2}{2}}_0^{>} + \order{T^2} = 1 - \frac{n-1}{2} \frac{I_d(b)}{K} + \order{T^2} \end{equation}\) as the length of the coarse-grained spin. The renormalized coupling constant in Eq. $\eqref{math:4}$ is now obtained from \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} K' &= b^{d-2} \zeta^2 \tilde{K} \\ &= b^{d-2} \qty[1 - \frac{n-1}{2} \frac{I_d(b)}{K}]^2 K \qty[1 + \frac{I_d(b)}{K}] \\ &= b^{d-2} K \qty[1 - \frac{n-2}{K} I_d(b) + \order{K^{-2}}] . \end{aligned} \label{math:5} \end{equation}\) We consider infinitesimal rescaling $b = 1 + \delta l$. The shell integral results in $I_d(b) = K_d \Lambda^{d-2} \delta l$, and the differential recursion relation of $\eqref{math:5}$ is \(\begin{equation} \dv{K}{l} = (d-2)K - (n-2) K_d \Lambda^{d-2} . \end{equation}\) Alternatively, the scaling of temperature $T = K^{−1}$ is \(\begin{equation} \dv{T}{l} = -(d-2)T + (n-2) K_d \Lambda^{d-2} T^2. \end{equation}\)

The behavior of temperature under RG changes drastically at $d = 2$. For $d < 2$, the linear flow is away from zero, indicating that the ordered phase is unstable and there is no broken symmetry. For $d > 2$, small $T$ flows back to zero, indicating that the ordered phase is stable.

If $d=2$, the flows will be controlled by the second ordered term. For $n > 2$ the flow is towards high temperatures, indicating that Heisenberg and higher spin models are disordered. The situation for $n = 2$ is ambiguous, and it can in fact be shown that $\dd T/ \dd l$ is zero to all orders. This special case will be discussed in more detail in the next section.

For $d > 2$ and $n > 2$, there is a phase transition at the fixed point, \(\begin{equation} T^{*} = \frac{\epsilon}{(n-2) K_d \Lambda^{d-2}} = \frac{2 \pi \epsilon}{n - 2} + \order{\epsilon^2}, \end{equation}\) where $\epsilon = d-2$ is used as a small parameter. The recursion relation at order of $\epsilon$ is \(\begin{equation} \dv{T}{l} = - \varepsilon T + \frac{n-2}{2\pi} T^2 . \end{equation}\) Stability of the fixed point is determined by the linearized recursion relation $\eval{\dv{\delta T}{l}}_{T^{*}} = \epsilon \delta T$, i.e. $y_t = \epsilon$. The thermal eigenvalue, and the resulting exponents $\nu = 1 / \epsilon$, and $\alpha = 2 - (2+\epsilon)/\epsilon \approx -2/\epsilon$, are independent of $n$ at this order.

The magnetic eigenvalue can be obtained by adding a term \(-\vb*{h} \int \dd[d]{\vb*{x}} \vb*{s}(\vb*{x})\) to the Hamiltonian. Under the action of RG, $h’ = b^d \zeta h \equiv b^{y_h}h$. After an infinitesimal rescaling, we get $y_h = 1 + \frac{n-3}{2(n-2)} \epsilon + \order{\epsilon^2}$, which does depend on $n$. Using exponent identities, we find $\eta = 2 + d - 2 y_h = \frac{\epsilon}{n-2}$. The actual values of the exponents calculated at this order are not very satisfactory.

Topological defects in the XY model

Let us examine the asymptotic behavior of the spin–spin correlation functions of the 2D XY model at high and low temperatures.

A high-temperature expansion for the correlation function for the XY model on a lattice is constructed from \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \ev{\vb*{s}_{\vb*{0}} \vdot \vb*{s}_{\vb*{r}}} &= \ev{\cos(\theta_{\vb*{0}} - \theta_{\vb*{r}})} = \frac{1}{Z} \prod_{i=1}^{N} \qty(\int_0^{2\pi} \frac{\dd{\theta_i}}{2\pi}) \cos(\theta_{\vb*{0}} - \theta_{\vb*{r}}) \ee^{K \sum_{\ev{i, j}} \cos(\theta_i - \theta_j)} \\ &= \frac{1}{Z} \prod_{i=1}^{N} \qty(\int_0^{2\pi} \frac{\dd{\theta_i}}{2\pi}) \cos(\theta_{\vb*{0}} - \theta_{\vb*{r}}) \prod_{\ev{i,j}} \qty[1 + K \cos(\theta_i - \theta_j) + \order{K^2}] . \end{aligned} \end{equation}\) The expansion for the partition function is similar, except for the absence of the factor \(\cos(\theta_{\vb*{0}} - \theta_{\vb*{r}})\). To the lowest order in K, each bond on the lattice contributes either a factor of one, or $K \cos(\theta_i - \theta_j)$. Since \(\begin{equation} \int_0^{2\pi} \frac{\dd \theta_1}{2 \pi} \cos(\theta_1 - \theta_2) = 0 , \end{equation}\) and \(\begin{equation} \int _ { 0 } ^ { 2 \pi } \frac { \dd \theta _ { 2 } } { 2 \pi } \cos ( \theta _ { 1 } - \theta _ { 2 } ) \cos ( \theta _ { 2 } - \theta _ { 3 } ) = \frac { 1 } { 2 } \cos ( \theta _ { 1 } - \theta _ { 3 } ) , \end{equation}\) the internal point must be connected to even number of bonds. With the integral over the end points \(\begin{equation} \int _ { 0 } ^ { 2 \pi } \frac { \dd \theta _ { \vb*{0} } \dd \theta _ { \vb*{r} } } { ( 2 \pi ) ^ { 2 } } \cos ( \theta _ { \vb*{0} } - \theta _ { \vb*{r} } ) ^ { 2 } = \frac { 1 } { 2 } , \end{equation}\) similarly, the external point should be connected to odd number of bonds. Note that the leading graph is the shortest path connecting the external points, \(\vb*{0}\) and \(\vb*{r}\). Since each bond along the path contributes $(K / 2)$, to lowest order, we get \(\begin{equation} \ev{\vb*{s}_{\vb*{0}} \vdot \vb*{s}_{\vb*{r}}} \approx \qty(\frac{K}{2})^{2r} = \ee^{-r / \xi} , \text{ with } \xi \approx \frac{1}{\ln(2 / K)} , \end{equation}\) and the disordered high-temperature phase is characterized by an exponential decay of correlations.

In the low-temperature expansion, we have an approximation, \(\begin{equation} - \beta \mathcal{H} = K \sum_{\ev{i, j}} \vb*{s}_i \vdot \vb*{s}_j \approx K \int \dd[d]{\vb*{x}} \qty[1 - \frac{1}{2} (\grad \theta)^2] , \end{equation}\) for small fluctuations around the ground state. Thus, the correlation function is \(\begin{equation} \ev{\vb*{s}_{\vb*{0}} \vdot \vb*{s}_{\vb*{r}}} = \frac { 1 } { Z } \int \mathcal{D} \theta \cos( \theta_{\vb*{0}} - \theta _ { \vb*{r} } ) \ee ^ { - \frac { K } { 2 } \int \dd[d]{\vb*{x}} ( \grad \theta ) ^ { 2 } } = \Re \ev{ \ee^{\ii ( \theta_{\vb*{0}} - \theta _ { \vb*{r} } ) } } = \ee ^ { - \frac { 1 } { 2 } \ev{( \theta_{\vb*{0}} - \theta _ { \vb*{r} } )^2} } . \end{equation}\) In two dimensions, the Gaussian fluctuations grow as \(\begin{equation} \frac { 1 } { 2 } \ev{( \theta_{\vb*{0}} - \theta _ { \vb*{r} } )^2} = \frac{1}{2 \pi K} \ln(\frac{r}{a}) , \end{equation}\) where $a$ is a short distance cutoff (of the order of the lattice spacing). Hence, at low temperatures, \(\begin{equation} \ev{\vb*{s}_{\vb*{0}} \vdot \vb*{s}_{\vb*{r}}} \approx \qty(\frac{r}{a})^{\frac{1}{2 \pi K}} , \end{equation}\) i.e. the decay of correlations is algebraic rather than exponential. Due to a critical point with self-similarity (no correlation length), this gives us low-temperature critical phase.

However, the arguments put forward above are not specific to the XY model. Any continuous spin model will exhibit exponential decay of correlations at high temperature, and a power law decay in a low-temperature Gaussian approximation. So, there will be a finite-temperature phase transition of 2D model with continuous symmetry ($n > 1$).

In the previous section, we talked about the nonlinear $\sigma$ model. The zero temperature fixed point in $d=2$ is unstable for all $n > 2$, but apparently stable for $n = 2$. The low-temperature phase of the XY model is said to possess quasi-long range order, as opposed to true long range order that accompanies a finite magnetization.

Next, let us study the mechanism for the disordering of the quasi-long range ordered phase. The gradient expansion describes the energy cost of small deformations around the ground state, and applies to configurations that can be continuously deformed to the uniformly ordered state. Kosterlitz and Thouless suggested that the disordering is caused by topological defects that can not be regarded as simple deformations of the ground state. Since the angle describing the orientation of a spin is undefined up to an integer multiple of $2\pi$, it is possible to construct spin configurations for which in going around a closed path the angle rotates by $2\pi n$. We call $n$ the topological charge enclosed by the path. Thus, the order parameter with compact group symmetry becomes \(\vb*{s}_{\vb*{x}} = (\cos(\theta_{\vb*{x}} + 2m\pi), \sin(\theta_{\vb*{x}} + 2n\pi))\) with \(\theta_{\vb*{x}} \in [0, 2\pi)\).

The elementary defect, or vortex, has unit charge. In completing a circle centered on the defect the orientation of the spin changes by $\pm 2 \pi$. For the circle far from the vortex core, the magnitude of the distortion is obtained from \(\begin{equation} \oint \grad \theta \vdot \dd s = \frac { \dd \theta } { \dd r } ( 2 \pi r ) = 2 \pi n , \quad \Rightarrow \quad \frac { \dd \theta } { \dd r } = \frac { n } { r } , \end{equation}\) and the direction is \(\begin{equation} \grad \theta = - \frac { n } { r } \vu*{r} \cp \vu*{z} = - n \curl ( \vu*{z} \ln r ) . \end{equation}\) This continuum approximation fails close to the core of the vortex, where the lattice structure is important.

The energy cost of a single vortex of charge $n$ has contributions from the core region, as well as from the relatively uniform distortions away from the center. The distinction between regions inside and outside the core is arbitrary, and we shall use a circle of radius $a$ to distinguish the two, i.e. \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \beta \mathcal{E}_{n} &= \beta \mathcal{E}^{0}_{n} (a) + \frac{K}{2} \int_a \dd[2]{\vb*{x}} (\grad \theta)^2 \\ &= \beta \mathcal{E}^{0}_{n} (a) + \frac{K}{2} \int_a^L (2\pi r \dd r) \qty(\frac{n}{r})^2 \\ &= \beta \mathcal{E}^{0}_{n} (a) + \pi K n^2 \ln(\frac{L}{a}) . \end{aligned} \end{equation}\) The dominant part of the energy comes from the region outside the core, and diverges with the size of the system, $L$. The large energy cost of defects prevents their spontaneous formation close to zero temperature. The partition function for a configuration with a single vortex is \(\begin{equation} Z _ { 1 } ( n ) \approx \qty( \frac { L } { a } ) ^ { 2 } \exp \qty[ - \beta \mathcal{E} _ { n } ^ { 0 } ( a ) - \pi K n ^ { 2 } \ln ( \frac { L } { a } ) ] = y _ { n } ^ { 0 } (a) \qty( \frac { L } { a } ) ^ { 2 - \pi K n ^ { 2 } } , \label{math:6} \end{equation}\) where $(L / a)^2$ results from the configurational entropy of possible vortex locations in a domain of area $L^2$. There is a competition between energy cost and configurational entropy. At low temperatures, \(K \gg \frac{2}{\pi n^2}\), energy dominates and $Z_1$ vanishes, which means that the single vortex is unfavorable. At high enough temperatures, $K < \frac{2}{\pi n^2}$, the entropy contribution is large enough to favor spontaneous formation of vortices. On increasing temperature, the first vortices to appear correspond to \(n = \pm 1\) at \(K_c = \frac{2}{\pi}\). Beyond this point there are many vortices in the system, and Eq. \(\eqref{math:6}\) is no longer useful.

The coupling \(K_c = \frac{2}{\pi}\) is a lower bound for the stability of the system to topological defects. This is because pairs (dipoles) of defects may appear at larger couplings. Consider a pair of charges $\pm 1$ at a separation $d$. The distortion field is approximatively \(\begin{equation} \grad \theta = \grad \theta_{+} + \grad \theta_{-} \approx \vb*{d} \vdot \grad(\frac{\vu*{r} \cp \vu*{z}}{r}) , \end{equation}\) so the energy cost is \(\begin{equation} \beta \mathcal{E}_d (a) = \beta \mathcal{E}^{0}_{d} (a) + \frac{K}{2} \int_a \dd[2]{\vb*{x}} (\grad \theta)^2 \approx \beta \mathcal{E}^{0}_{d} (a) + \pi K d^2 \qty(\frac{1}{2 a^2} - \frac{1}{2 L^2}) . \end{equation}\) This is a finite energy, and hence dipoles appear with the appropriate Boltzmann weight at any temperature. The low-temperature phase should thus be visualized as a gas of tightly bound dipoles. The number and the size of dipoles increase with temperature, and the high-temperature state is a plasma of unbound vortices.

To describe the transition between the two regimes, we need to properly account for the interactions between vortices. The distortion field \(\vb*{u} \equiv \grad{\theta}\), in the presence of a collection of vortices, is similar to the velocity of a fluid. In the absence of vortices, the flow has no vorticity and it is a gradient field, i.e. \(\vb*{u} = \vb*{u}_0 = \grad{\phi}\), and \(\curl{\vb*{u}} = 0\). In the presence of vortices, Stokes’ theorem tells us \(\begin{equation} \oint \vb*{u} \vdot \dd{\vb*{s}} = 2 \pi \sum_i n_i = \int \dd[2]{\vb*{x}} \vu*{z} \vdot (\curl{\vb*{u}}) , \end{equation}\) and we can set \(\begin{equation} \curl{\vb*{u}} = 2 \pi \vu*{z} \sum_i n_i \delta^2 (\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}_i) , \end{equation}\) describing a collection of vortices of charge \(\{n_i\}\) at locations \(\{\vb*{x}_i\}\). The 2D vector field is the sum of the gradient field and the curl of vector field \(\vb*{u} = \vb*{u}_0 + \vb*{u}_1 = \grad{\phi} - \curl(\vu*{z} \psi)\), leading to \(\begin{equation} \curl{\vb*{u}} = \vu*{z} \laplacian{\psi} , \quad \Rightarrow \quad \laplacian{\psi} = 2 \pi \sum_i n_i \delta^2 (\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}_i) . \end{equation}\) Thus, the solution is simply \(\begin{equation} \psi(\vb*{x}) = \sum_i n_i \ln(\abs{\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}_i}) . \end{equation}\)

Firstly, since following an integration by parts, we notice \(\begin{equation} - \int \dd[2]{\vb*{x}} \grad{\phi} \vdot \curl{\vu*{z} \psi} = \int \dd[2]{\vb*{x}} \phi \div(\curl{\vu*{z} \psi}) = 0 . \end{equation}\) Secondly, by noting that \(\grad{\psi} = (\pp_x \psi, \pp_y \psi, 0)\) and \(\curl{\vu*{z} \psi}= (-\pp_y \psi, \pp_x \psi, 0)\) are orthogonal vectors of equal length. Hence \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \frac{K}{2} \int \dd[2]{\vb*{x}} (\curl{\vu*{z} \psi})^2 &= \frac{K}{2} \int \dd[2]{\vb*{x}} (\grad{\psi})^2 = - \frac{K}{2} \int \dd[2]{\vb*{x}} \psi \laplacian{\psi} \\ &= - \frac{K}{2} \int \dd[2]{\vb*{x}} \Big[ \sum_i n_i \ln{\abs{\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}_i}} \Big] \Big[ 2 \pi \sum_j n_j \delta^{2} (\abs{\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}_j}) \Big] \\ &= - 2 \pi^2 K \sum_{i, j} n_i n_j C(\vb*{x}_i - \vb*{x}_j) \\ &= \sum_i \beta \mathcal{E}_{n_i}^{0} - 4 \pi^2 K \sum_{i < j} n_i n_j C(\vb*{x}_i - \vb*{x}_j) ,\\ \end{aligned} \end{equation}\) where \(C(\vb*{x}) = \ln(\abs{\vb*{x}}) / (2\pi)\) is the two-dimensional Coulomb potential and \(\beta \mathcal{E}_{n_i}^{0}\) is the self-interaction (core energy) of a vortex. Thus, the energy cost is \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \beta \mathcal{H} &= \frac{K}{2} \int \dd[2]{\vb*{x}} (\grad{\theta})^2 \\ &= \frac{K}{2} \int \dd[2]{\vb*{x}} \qty[\grad{\phi} - \curl{\vu*{z} \psi}]^2 \\ &= \frac{K}{2} \int \dd[2]{\vb*{x}} \qty[(\grad{\phi})^2 - 2 \grad{\phi} \vdot \curl{\vu*{z} \psi} + (\curl{\vu*{z} \psi})^2]^2 \\ &= \frac{K}{2} \int \dd[2]{\vb*{x}} (\grad{\phi})^2 + \sum_i \beta \mathcal{E}_{n_i}^{0} - 4 \pi^2 K \sum_{i < j} n_i n_j C(\vb*{x}_i - \vb*{x}_j) . \end{aligned} \end{equation}\)

In low temperature, the configuration space of the XY model can be partitioned into different topological segments. Thus, the partition function can be approximated as \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} Z &= \prod_i \int_0^{2\pi} \frac{\dd{\theta_i}}{2 \pi} \exp \qty[K \sum_{\ev{i, j}} \cos(\theta_i - \theta_j)] \\ & \propto \int \mathcal{D} \phi(\vb*{x}) \ee^{- \frac{K}{2} \int \dd[2]{\vb*{x}} (\grad{\phi})^2} \sum_{\{n_i\}} \int \dd[2]{\vb*{x}_i} \ee^{- \sum_i \beta \mathcal{E}^0_{n_i} + 4 \pi^2 K \sum_{i < j} n_i n_j C(\vb*{x}_i - \vb*{x}_j)} \\ & \equiv Z_{\text{s.w.}} Z_{Q} , \end{aligned} \label{math:7} \end{equation}\) where \(Z_{\text{s.w.}}\) is the Gaussian partition function of spin waves, and $Z_Q$ is the contribution of vortices. The latter describes a grand canonical gas of charged particles, interacting via the two dimensional Coulomb interaction. We further simplify the problem by considering only the elementary excitations with \(n_i = \pm 1\), which are most likely at low temperatures due to their lower energy. Setting $y_0 \equiv \exp[- \beta \mathcal{E}_{\pm 1}^{0}]$, \(\begin{equation} Z_Q = \sum_{N=0}^{\infty} y_0^N \int \prod_{i=1}^N \dd[2]{\vb*{x}_i} \exp \qty[4 \pi^2 K \sum_{i < j} q_i q_j C(\vb*{x}_i - \vb*{x}_j) ] , \label{math:8} \end{equation}\) where \(q_i = \pm 1\), and \(\sum_i q_i = 0\).

Renormalization group for the Coulomb gas

The two partition functions in Eq. $\eqref{math:7}$ are independent and can be calculated separately. As the Gaussian partition function is analytic, any phase transitions of the XY model must originate in the Coulomb gas. The high temperature phase and the low temperature phase can be distinguished by examining the interaction between two external test charges at a large separation $X$.

Now we shall compute the effective interaction between two external charges at \(\vb*{x}\) and \(\vb*{x}'\), perturbatively in the fugacity $y_0$. To lowest order, we need to include configurations with two internal charges (at \(\vb*{y}\) and \(\vb*{y}'\)), and \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \ee^{-\beta \mathcal{V} (\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}')} &= \ev{ \ee^{- 4 \pi^2 K C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}')} } \\ &= \frac{\sum_{N=0}^{\infty} y_0^N \prod_i^N \int \dd[2]{\vb*{y}_i} \ee^{- 4 \pi^2 K C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}')} \ee^{4 \pi^2 K \sum_i q_i C (\vb*{x} - \vb*{y}_i)} \ee^{- 4 \pi^2 K \sum_i q_i C (\vb*{x}' - \vb*{y}_i)} \ee^{ 4 \pi^2 K \sum_{i < j} q_i q_j C (\vb*{y}_i - \vb*{y}_j)}}{ \sum_{N=0}^{\infty} y_0^N \prod_i^N \int \dd[2]{\vb*{y}_i} \ee^{4 \pi^2 K \sum_{i < j} q_i q_j C (\vb*{y}_i - \vb*{y}_j)}} \\ &= \ee^{- 4 \pi^2 K C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}')} \qty[ 1 + y_0^2 \int \dd[2]{\vb*{y}} \dd[2]{\vb*{y}'} \qty(\ee^{4 \pi^2 K D(\vb*{x}, \vb*{x}'; \vb*{y},\vb*{y}')} - 1) \ee^{- 4 \pi^2 K C(\vb*{y} - \vb*{y}')} + \order{y_0^4}] , \end{aligned} \end{equation}\) where \(D(\vb*{x}, \vb*{x}'; \vb*{y},\vb*{y}')\) is the interaction between the internal and external dipoles. Supposing that the separation \(\vb*{r} = \vb*{y}' - \vb*{y}\) is small, and with \(\vb*{y} = \vb*{R} - \vb*{r} / 2\) and \(\vb*{y}' = \vb*{R} + \vb*{r} / 2\), the dipole–dipole interaction becomes \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} D(\vb*{x}, \vb*{x}'; \vb*{y}, \vb*{y}') &= C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{y}) - C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{y}') - C(\vb*{x}' - \vb*{y}) + C(\vb*{x}' - \vb*{y}') \\ &= C(\vb*{x} -\vb*{R} + \frac{\vb*{r}}{2}) - C(\vb*{x} -\vb*{R} - \frac{\vb*{r}}{2}) - C(\vb*{x}' -\vb*{R} + \frac{\vb*{r}}{2}) + C(\vb*{x}' -\vb*{R} - \frac{\vb*{r}}{2}) \\ &= - \vb*{r} \vdot \grad_{\vb*{R}} C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{R}) + \vb*{r} \vdot \grad_{\vb*{R}} C(\vb*{x}' - \vb*{R}) + \order{r^3} \\ &= - \vb*{r} \vdot \grad_{\vb*{R}}(C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{R}) - C(\vb*{x}' - \vb*{R})) + \order{r^3} . \end{aligned} \end{equation}\) To the same order, \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \ee^{4 \pi^2 K D(\vb*{x}, \vb*{x}'; \vb*{y}, \vb*{y}')} - 1 = & - 4 \pi^2 K \vb*{r} \vdot \grad_{\vb*{R}} (C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{R}) - C(\vb*{x}' - \vb*{R})) \\ & + 8 \pi^4 K^2 \qty[\vb*{r} \vdot \grad_{\vb*{R}} (C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{R}) - C(\vb*{x}' - \vb*{R}))]^2 + \order{r^3} . \end{aligned} \end{equation}\) With the integral, \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} & \int \dd[2]{\vb*{R}} [\grad_{\vb*{R}}(C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{R}) - C(\vb*{x}' - \vb*{R}))]^2 \\ =& - \int \dd[2]{\vb*{R}} (C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{R}) - C(\vb*{x}' - \vb*{R})) \qty(\laplacian{C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{R})} - \laplacian{C(\vb*{x}' - \vb*{R})}) \\ =& - \int \dd[2]{\vb*{R}} (C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{R}) - C(\vb*{x}' - \vb*{R})) \qty(\delta^2 {(\vb*{x} - \vb*{R})} - \delta^2 {(\vb*{x}' - \vb*{R})}) \\ =& \ 2 C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}') - 2 C(0) , \end{aligned} \end{equation}\) and the symmetry, we have \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} &\int \dd[2]{\vb*{y}} \dd[2]{\vb*{y}'} \qty(\ee^{4 \pi^2 K D(\vb*{x}, \vb*{x}'; \vb*{y}, \vb*{y}')} - 1) \ee^{-4 \pi K C(\vb*{y} - \vb*{y}')} \\ =& 0 + \frac{(4\pi^2 K)^2}{2} \int \dd{r} r^3 \ee^{-4\pi^2 K C(r)} \frac{2\pi}{2} \int \dd[2]{\vb*{R}} [\grad_{\vb*{R}}(C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{R}) - C(\vb*{x}' - \vb*{R}))]^2 \\ =& 4 \pi^2 \qty(4 \pi^3 K^2 \int \dd{r} r^3 \ee^{- 4\pi^2 K C(r)}) C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}') . \end{aligned} \end{equation}\) Thus, the effective interaction becomes \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \ee^{-\beta \mathcal{V} (\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}')} &= \ee^{- 4\pi^2 K C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}')} \qty[1 + 4 \pi^2 \qty(4 \pi^3 K^2 y_0^2 \int \dd{r} r^3 \ee^{- 4\pi^2 K C(r)}) C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}') + \order{y_0^4}] \\ &= \ee^{- 4\pi^2 K C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}')} \ee^{4 \pi^2 \qty(4 \pi^3 K^2 y_0^2 \int \dd{r} r^3 \ee^{- 4\pi^2 K C(r)}) C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}')} \\ &\equiv \ee^{- 4\pi^2 K_{\text{eff}} C(\vb*{x} - \vb*{x}')} . \end{aligned} \end{equation}\) The short distance divergence can again be absorbed into a proper cutoff with \(C(x) \rightarrow \ln(x / a) / (2 \pi)\), so \(K_{\text{eff}}\) becomes \(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} K_{\text{eff}} &= K - 4 \pi^3 K^2 y_0^2 \int \dd{r} r^3 \ee^{- 4\pi^2 K \ln(r / a) / (2 \pi)} \\ &= K - 4 \pi^3 K^2 y_0^2 \int \dd{r} r^3 \qty(\frac{r}{a})^{-2 \pi K} \\ &= K - 4 \pi^3 K^2 y_0^2 a^{2 \pi K} \int_{a}^{\infty} \dd{r} r^{3 - 2\pi K} . \end{aligned} \label{math:9} \end{equation}\)

We have thus evaluated the dielectric constant of the medium, \(\epsilon = K / K_{\text{eff}}\), perturbatively to order of $y_0^2$. However, the integral is not small when \(K < K_c = 2 / \pi\), which marks the breakdown of the perturbation theory. Using the experience gained from Landau–Ginzburg model for $d < 4$, we shall reorganize the perturbation series into a renormalization group for the parameters $K$ and $y_0$.

To construct an RG for the Coulomb gas, note that the partition function for the system in Eq. $\eqref{math:8}$ involves two parameters \((K, y_0)\), and has an implicit cutoff $a$, related to the minimum separation between vortices. In order to do coarse graining, we increase the core size from $a$ to $ba$, modifying the core energy, hence $y_0$, and the interaction parameter $K_0$. From Eq. $\eqref{math:6}$ and Eq. $\eqref{math:9}$, the change in fugacity is \(\begin{equation} \tilde{y}_0 (ba) = b^{2 - \pi K} y_0 (a) , \end{equation}\) and the change in interaction parameter is \(\begin{equation} \tilde{K} = K - 4 \pi^3 K^2 y_0^2 a^{2 \pi K} \int_a^{ba} \dd{r} r^{3 - 2 \pi K} . \label{math:10} \end{equation}\)

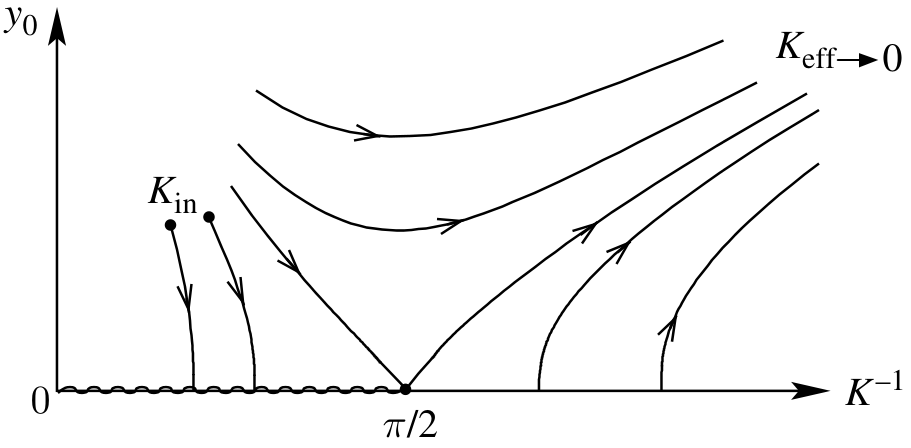

By choosing an infinitesimal \(b = \ee^{l} \approx 1 + l\), Eq. $\eqref{math:10}$ becomes \(\begin{equation} \dv{K}{l} = - 4 \pi^3 K^2 a^4 y_0^2 + \order{y_0^4} . \end{equation}\) Including the fugacity, the recursion relations are \(\begin{equation} \left\{ \begin{aligned} & \dv{K^{-1}}{l} = 4 \pi^3 a^4 y_0^2 + \order{y_0^4} \\ & \dv{y_0}{l} = (2 - \pi K) y_0 + \order{y_0^3} , \end{aligned} \right. \label{math:11} \end{equation}\) originally obtained by Kosterlitz. At smaller values of $K^{-1}$ (high temperatures) $y_0$ is relevant, while at lower temperatures it is irrelevant. At low temperatures and small $y_0$, flows terminate on a fixed line at $y_0 = 0$ and \(K_{\text{eff}} \geqslant 2 / \pi\). This is the insulating phase (gas phase) in which only dipoles of finite size occur. The strength of the effective Coulomb interaction is given by the point on the fixed line that the flows terminate on. Flows not terminating on the fixed line asymptote to larger values of $K^{−1}$ and $y_0$, where perturbation theory breaks down. This is the signal of the high-temperature phase with an abundance of vortices.

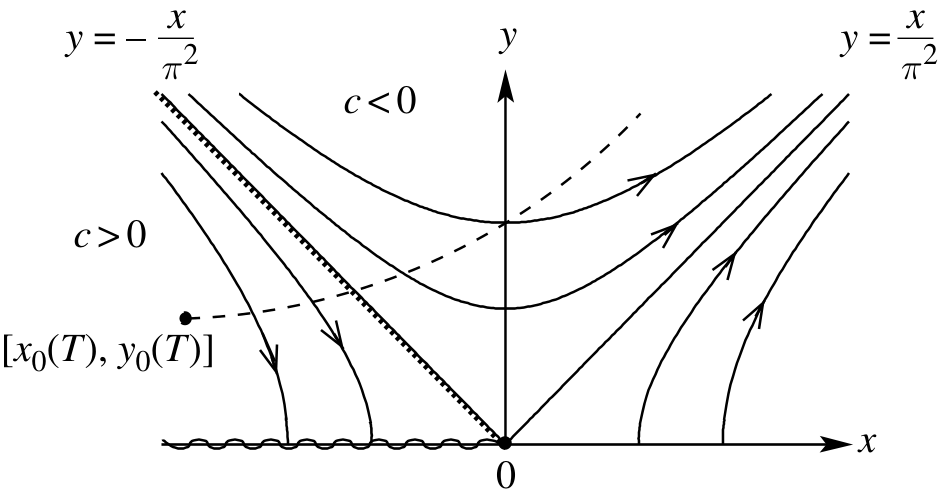

To find the critical behavior at the transition, expand the recursion relations in the vicinity of the fixed point $(K_c^{-1} = \pi / 2, y_0 = 0)$ by setting $x = K^{-1} - \pi / 2$, and $y = y_0 a^2$. To lowest order, Eqs. $\eqref{math:11}$ simplify to \(\begin{equation} \left\{ \begin{aligned} & \dv{x}{l} = 4 \pi^3 y^2 + \order{x y^2, y^4} \\ & \dv{y}{l} = \frac{4}{\pi} x y + \order{x y^2, y^3} . \end{aligned} \right. \label{math:12} \end{equation}\) The recursion relations are inherently nonlinear in the vicinity of the fixed point. First note that Eqs. $\eqref{math:12}$ imply \(\begin{equation} \dv{x^2}{l} = 8 \pi^3 y^2 x = \pi^4 \dv{y^2}{l} , \quad \Rightarrow \quad x^2 - \pi^4 y^2 = c. \end{equation}\) The RG flows thus proceed along hyperbolas characterized by different values of $c$. For $c > 0$, the focus of the hyperbola is along the $y$-axis, and the flows proceed to \((x, y) \rightarrow (\infty, \infty)\) (plasma phase). For $c < 0$, the foci are along the $x$-axis, and have two branches in the half plane $y \geqslant 0$: the trajectories for $x < 0$ flow to the fixed line (gas phase), while those for $x < 0$ flow to infinity (plasma phase). The critical trajectory separating flows to zero and infinite $y$ corresponds to $c = 0$, i.e. $x_c = - \pi^2 y_c$. Therefore, a small but finite fugacity $y_0$ reduces the critical temperature to $K_c^{-1} = \pi / 2 - \pi^2 y_0 a^2 + \order{y_0^2}$.

In terms of the original XY model, the low-temperature critical phase is characterized by a line of fixed points with \(K_{\text{eff}} = \lim_{l \rightarrow \infty} K(l) \geqslant 2 / \pi\). There is no correlation length at a fixed point, and indeed the correlations in this phase decay as a power law, \(\ev{\vb*{s}_{\vb*{0}} \vdot \vb*{s}_{\vb*{r}}} \sim 1 / r^{d - 2 + \eta}\), with \(\eta = 1 / (2 \pi K_{\text{eff}}) \leqslant 1 / 4\). Since the parameter $c$ is negative in the low temperature phase, and vanishes at the critical point, we can set it to $c = x^2_0 - \pi^4 y_0^2 = - b^2 (T_c - T)$ close to the transition. Under renormalization, such trajectories flow to a fixed point at $y = 0$, and $x = - b \sqrt{T_c - T}$. Thus in the vicinity of transition, the effective interaction parameter \(\begin{equation} K_{\text{eff}} = \frac{2}{\pi} - \frac{4}{\pi^2} \lim_{l \rightarrow \infty} x(l) = \frac{2}{\pi} + \frac{4 b}{\pi^2} \sqrt{T_c - T} \end{equation}\) has a square root singularity with universal jump. The stiffness \(K_{\text{eff}}\), can be measured in experiments on superfluid films and can verify the above results.

Correlations decay exponentially in the high-temperature disordered phase. The parameter $c = x^2 - \pi^4 y^2 = b^2 (T_c - T)$ is now positive all along the hyperbolic trajectory. The recursion relation for $x$, \(\begin{equation} \dv{x}{l} = 4 \pi^3 y^2 = \frac{4}{\pi} (x^2 + b^2 (T - T_c)) , \end{equation}\) can be integrated to give \(\begin{equation} \frac{\dd x}{x^2 + b^2 (T - T_c)} = \frac{4}{\pi} \dd{l} , \quad \Rightarrow \quad \frac{1}{b \sqrt{T - T_c}} \arctan(\frac{x}{b \sqrt{T - T_c}}) = \frac{4}{\pi} l . \end{equation}\) The contribution of the initial point to the left-hand side of the above equation can be left out if \(x_0 \propto (T - T_c) \ll 1\). The integration has to be stopped when \(x(l) \sim y(l) \sim 1\), since the perturbative calculation is no longer valid beyond this point. This occurs for a value of \(\begin{equation} l^{*} \approx \frac{\pi}{4 b \sqrt{T - T_c}} \frac{\pi}{2} , \end{equation}\) where we have used \(\arctan(1 / (b \sqrt{T - T_c})) \approx \arctan(\infty) = \pi / 2\). The resulting correlation length is \(\begin{equation} \xi \approx a \ee^{l^{*}} \approx a \exp(\frac{\pi^2}{8 b \sqrt{T - T_c}}) . \end{equation}\) Unlike any of the transitions encountered so far, the divergence of the correlation length is not through a power law. This is a consequence of the nonlinear nature of the recursion relations in the vicinity of the fixed point.

On approaching the transition from the high-temperature side, the singular part of the free energy, \(\begin{equation} f_{\text{sing}} \propto \xi^{-2} \propto \exp(- \frac{\pi^2}{4 b \sqrt{T - T_c}}) , \end{equation}\) has only an essential singularity. All derivatives of this function are finite at $T_c$. Thus the predicted heat capacity is quite smooth at the transition.

The Kosterlitz–Thouless picture of vortex unbinding has found numerous applications in two-dimensional systems such as superconducting and superfluid films, thin liquid crystals, Josephson junction arrays, electrons on the surface of helium films, etc. Perhaps more importantly, the general idea of topological defects has had much impact in understanding the behavior of many systems. The theory of two-dimensional melting developed in the next sections is one such example.

-

Kardar, Mehran. 2007. Statistical Physics of Fields. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ↩